#1

Behaviour Incident Reporting App

AI-Powered Incident Recording & Behaviour Support System for Schools and Children's Homes.

Behaviour Smart empowers teachers, SLT, and carers to track behaviour in real time, analyse trends with AI, and create targeted interventions that improve outcomes for students and young people.

Your All-in-One Behaviour Management System for Schools

Your All-in-One Behaviour Management System for Schools

Smooth transition, minimal disruption. Behaviour Smart is built with change management at its core, so moving from paper or legacy systems is quick, fully supported, and stress-free for your staff.

Your All-in-One Behaviour Management System for Schools

Smooth transition, minimal disruption. Behaviour Smart is built with change management at its core, so moving from paper or legacy systems is quick, fully supported, and stress-free for your staff.

Why Choose Behaviour Smart?

Behaviour Smart is not just about collecting data or manually analysing data. Behaviour Smart AI is a powerful tool that empowers schools and children's homes to turn every recorded incident into meaningful action, improving outcomes for students, young people and staff.

Beyond Data Collection: Most systems stop at recording behaviour. Behaviour Smart goes further, analysing patterns, identifying triggers, and providing instant, practical recommendations that make a real difference.

Why Choose Behaviour Smart?

Behaviour Smart is not just about collecting data or manually analysing data. Behaviour Smart AI is a powerful tool that empowers schools and children's homes to turn every recorded incident into meaningful action, improving outcomes for students, young people and staff.

Beyond Data Collection: Most systems stop at recording behaviour. Behaviour Smart goes further, analysing patterns, identifying triggers, and providing instant, practical recommendations that make a real difference.

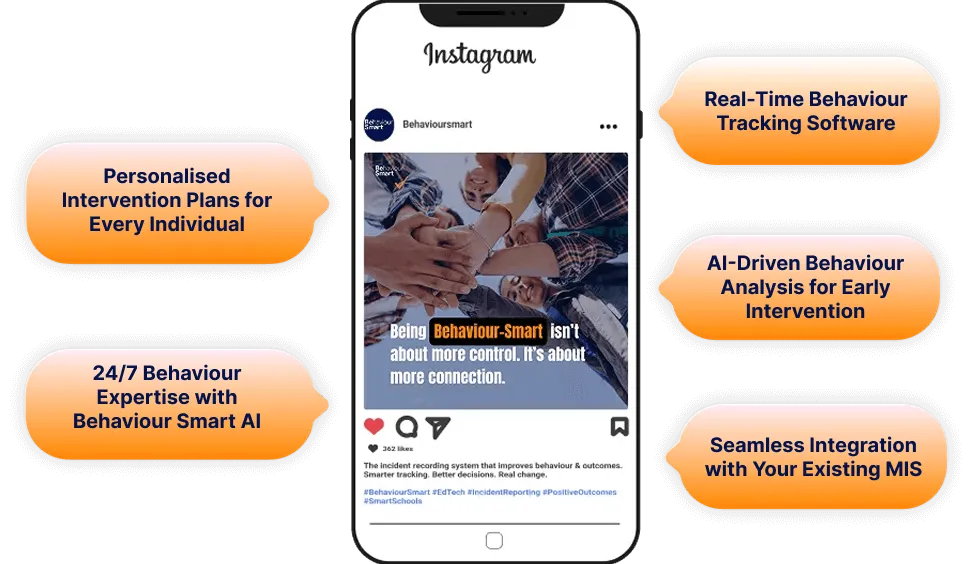

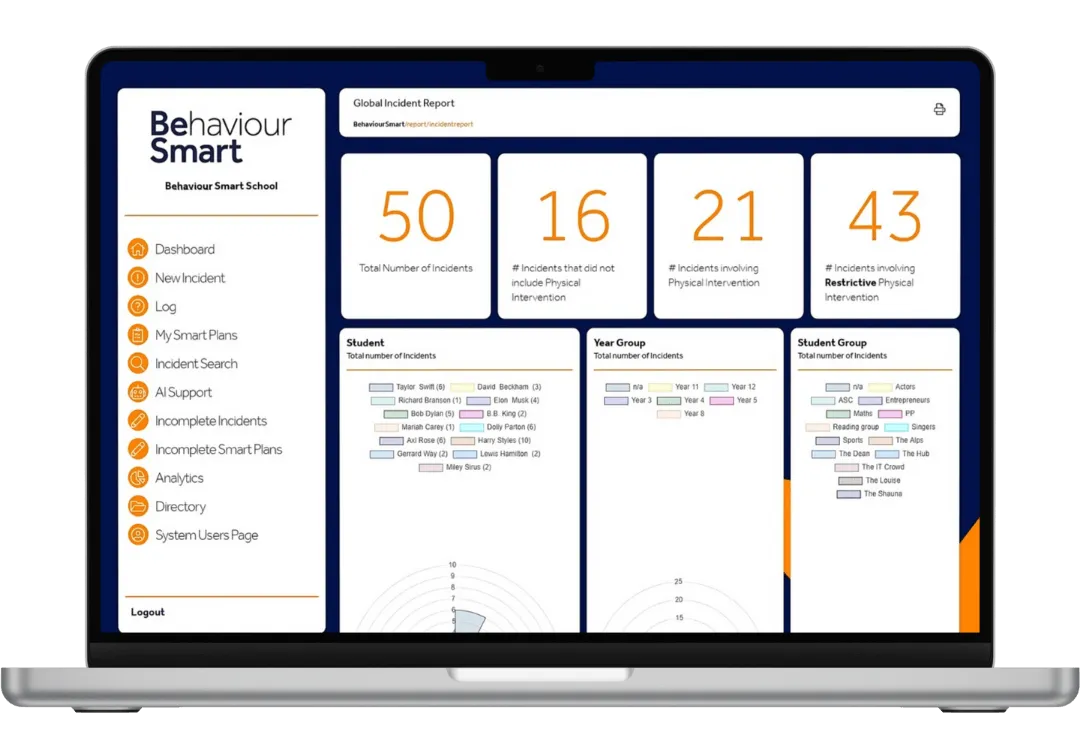

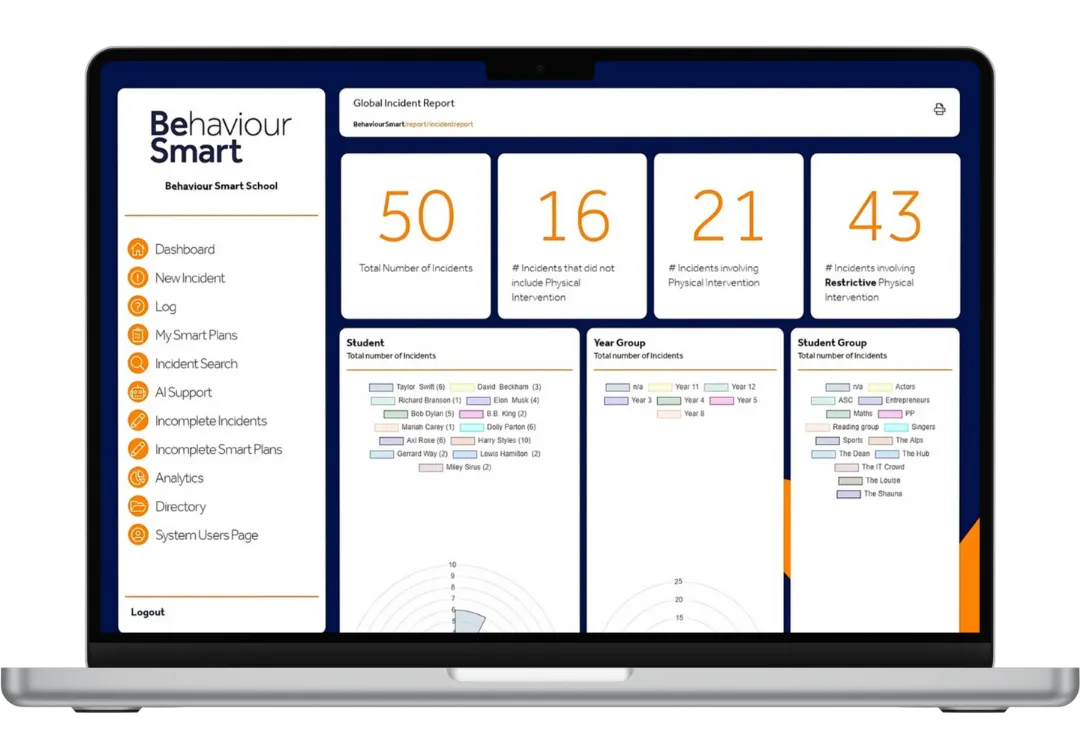

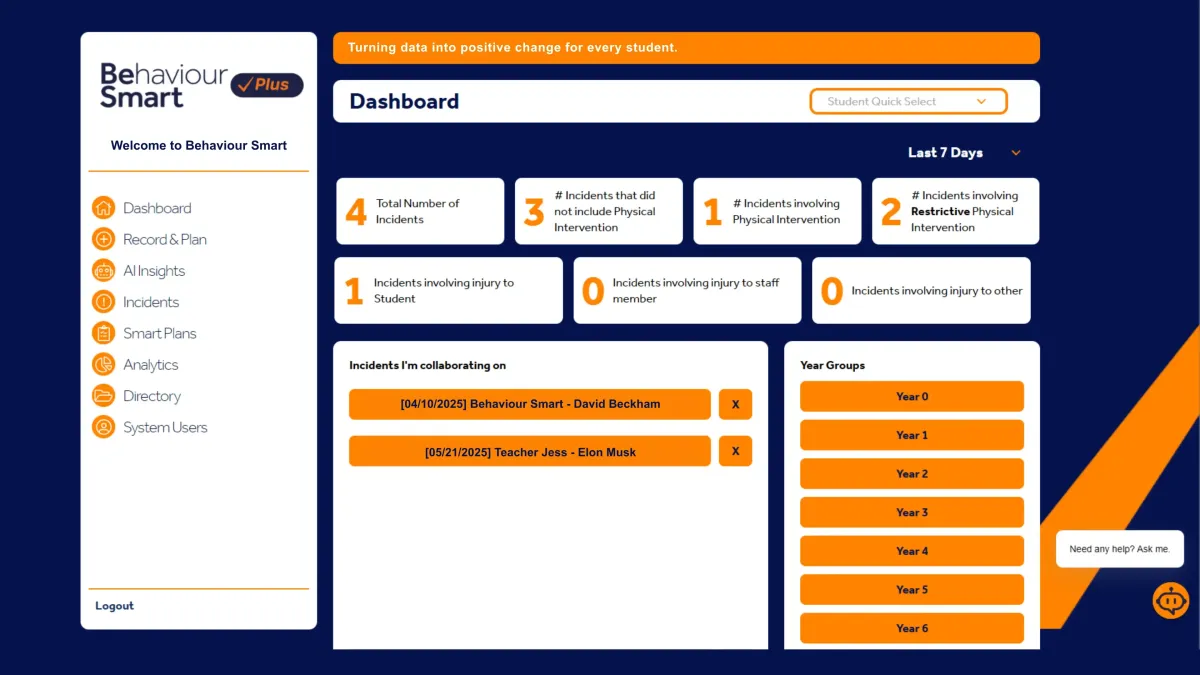

Real-Time Behaviour Tracking Software

Log incidents instantly from any device and see behaviour data updates across classes, year groups or key worker groups. Powerful dashboards reveal frequency, location and time-of-day trends so you can intervene before issues escalate.

AI-Driven Behaviour Analysis for Early Intervention

Our machine-learning models identify emerging behaviour patterns and recommend evidence-based strategies. Proactive alerts help staff act quickly, reducing repeat incidents and improving classroom climate.

Cyber Essentials Certified

We’re proud to be Cyber Essentials certified, demonstrating our commitment to implementing the UK Government’s most essential cybersecurity controls.

The Cyber Essentials scheme outlines a set of baseline technical measures designed to protect organisations, including schools and children’s homes, from common online threats. It helps safeguard the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of sensitive data stored on internet-connected devices.

This certification shows that Behaviour Smart is serious about data protection, online safety, and cyber resilience giving you confidence that your information is secure.

Create Effective Behaviour Support Plans

Upon completing an incident report, the platform automatically generates and updates tailored behaviour support plans for each student or young person. These personalised plans equip staff with consistent, effective strategies to manage behaviour and encourage positive change.

Response Effectiveness

Ratings

Staff can rate the effectiveness of their chosen responses to distressed behaviour. Behaviour Smart then analyses these ratings, providing an independent effectiveness score for each response empowering staff to make evidence-based adjustments.

24/7 Behaviour Expertise with Behaviour Smart AI

Our AI acts as a round-the-clock behaviour expert, delivering real-time feedback on individual incidents, specific individuals, or your entire service. This immediate support helps staff understand behaviour patterns and proactively address emerging issues.

Seamless Integration with Your Existing MIS

Behaviour Smart connects to popular UK MIS platforms, saving staff time and ensuring behaviour, attendance and safeguarding data stay in sync.

Personalised Intervention Plans for Every Individual

Generate tailored behaviour intervention plans in one click. Track progress, share goals with parents and carers, and automatically update support strategies as new data rolls in.

Revolutionise Behaviour Tracking with Our AI-Powered System

Revolutionise behaviour tracking with an AI-powered system built for schools, special provisions, and care settings. Log incidents in seconds, identify patterns instantly, and generate SMART behaviour plans strengthening safeguarding, reducing disruption, and providing inspection-ready evidence.

Customer Reviews

See what clients say about Behaviour Smart’s behavioural science consultancy, training, and solutions.

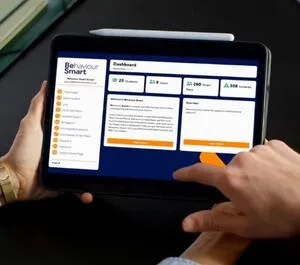

See Behaviour Smart in Action

Explore the Behaviour Smart dashboard and discover how our AI-powered behaviour management tool helps UK schools track, analyse, and improve student behaviour.

How Does Behaviour Smart Improves Behaviour?

Here’s how our platform makes a difference

Reflective Incident Reporting

When staff complete an incident report, they’re prompted to reflect on the event and consider alternative strategies for future situations. Unsure what to try next time? Behaviour Smart AI is on hand to suggest effective responses, helping staff expand their toolkit.

Post-Incident Learning

At Behaviour Smart, we recognise that post-incident learning is key to effective behaviour support. Our structured approach, grounded in extensive research, not only reduces the chance of repeated incidents but also supports sustained, long-term behaviour improvement.

Insightful Data Analysis

Behaviour Smart offers powerful data analysis and incident search features, enabling schools and children’s homes to identify trends, spot patterns, and make informed, evidence-based decisions that improve outcomes for everyone.

Effectiveness Ratings

Staff can rate the effectiveness of their chosen responses to distressed behaviour. Behaviour Smart then analyses these ratings, providing an independent effectiveness score for each response, empowering staff to make evidence-based adjustments.

Behaviour Smart Packages

Discover the Behaviour Smart Plan That’s Right for You

AI Behaviour Management in Mainstream Schools

Behaviour Smart Lite isn’t just another behaviour tracking tool, it’s a purpose-built, AI-powered system designed specifically for UK mainstream schools. From instant incident logging to real-time behaviour insights and MIS integration, it helps schools manage behaviour smarter, faster, and with real impact.

AI Behaviour Management in Mainstream Schools

Behaviour Smart Lite isn’t just another behaviour tracking tool, it’s a purpose-built, AI-powered system designed specifically for UK mainstream schools. From instant incident logging to real-time behaviour insights and MIS integration, it helps schools manage behaviour smarter, faster, and with real impact.

AI Behaviour Management and Support for Care Settings

Behaviour Smart Care is a powerful, AI-driven behaviour management and incident recording system built specifically for care environments like children’s homes, supported living, and residential care. Fast to use, secure by design, and made for frontline care professionals.

Frequently Asked Questions

What does Behaviour Smart do?

Behaviour Smart is an AI-powered incident recording and reporting system that improves behaviour in schools and children’s homes.

Who can use Behaviour Smart?

Behaviour Smart is suitable for:

• Behaviour Smart Care is suitable for children’s homes, residential care homes, nursing and dementia care, respite care, and supported living

• Behaviour Smart Lite is designed for mainstream schools (early years, primary, secondary, post-16, higher education)

• Behaviour Smart Plus is designed for mainstream schools, specialist settings: learning disabilities, SEMH, ASC, physical disabilities, PRUs, independent special schools, alternative provisions

What features are included in Behaviour Smart?

• AI-powered behaviour analysis

• Incident recording & reporting tools

• Behaviour support plan generation

• MIS integration via Wonde

• Real-time feedback & post-incident learning tools

• Continuous Professional Development resources

Does Behaviour Smart integrate with school MIS systems?

Yes! it integrates seamlessly with Management Information Systems via Wonde for smooth data import (students, staff, parents).

Is Behaviour Smart GDPR compliant and secure?

Yes! Behaviour Smart is Cyber Essentials certified, GDPR and DPA 2018 compliant, with data protection managed by Veritau.

Do you provide training for staff?

Yes! Free onboarding training is included, with ongoing training available on request.

What support is available for Behaviour Smart users?

Support is available via:

• Help pages

• Website chat

90% of inquiries are handled instantly by Sophie, our AI bot. If Sophie can’t help, you can book an appointment with a team member.

Are there tutorial videos for Behaviour Smart?

Yes! The Help Centre includes tutorial videos for:

• Package overviews

• Setup steps

• Using the Behaviour Clicker

• Logging behaviour

• Incident reporting (with or without intervention)

See real‑time results and insights from real practice to real change.

Discover how Behaviour Smart transforms incident data into personalised action, reflection, and effective behaviour plans. Book a free demo now

AI-powered behaviour management and the #1 behaviour tracking app for UK schools.

© Copyright 2019 - 2025 Behaviour Smart Ltd.

All Rights Reserved.

© Copyright 2019 - 2025 Behaviour Smart Ltd.

All Rights Reserved.